Fri, 27 June 2014

Comics are an inherently overlooked medium. I don’t necessarily mean that in the sense of cultural appreciation––we have the multi-billion dollar Marvel cinematic universe to prove that isn’t true––I mean as a reader reading comics. Being overlooked is the point, however. A thoughtfully crafted page layout naturally guides the eye from one panel to the next, causing your brain to not even notice that the images are static and, perhaps, nonsensical when taken out of context. Comics rely on the fact that a reader’s brain fills in the gaps between the panels––formally called gutters––with action and camera moves so that the next panel does make sense. Part of that trick is to give the reader just enough information to get the gist and keep moving. As you can guess, the artist can easily manipulate this to either slow down or speed up a reader, depending on what the story (or creator) demands. As quickly as it takes to read a comic, the amount of work that goes into creating not only a book, not only a page, but a panel is painstaking (though, panel composition also involves a lot of instinct, too). Think of it this way: in a movie, a filmmaker gets twenty-four frames per second to show the viewer a single shot. Not to be patronizing, but that is, again, twenty-four still images in a single second of on-screen time. That’s 1,440 still images per minute of film. Furthermore, a shot in a movie can last a few seconds to a minute or two (or five or ten), which means thousands of still images could come together to show movement and progression of character and story. A panel is pretty much (with exceptions, of course) the equivalent of a single shot in a film. Again, not to patronize, but a panel is a single drawing.

What a comic artist has to do is pick the one image from the entire range of possibilities––a range that would normally be shown in film––and pick the exactly right one to do the same thing as an entire shot. Of course, this isn’t a perfect science, but no matter the level of care or artistry, it is a thoughtful one. No matter what, a comicker has to boil every panel down to a moment––one that best suits the goals of that panel as well as serves the needs of the page and also serves the needs of the book. It’s a scary business if you think about it like that and expanding it to a page––trying to capture that perfect image between three and six times per page, sometimes more. But most readers soar over panels, linking the actions and stories between them naturally and easily so that they see a fully fleshed out movie in their heads, full of foley, dialogue, and background music.

Many comics readers are also artistically inclined and, in the age of easy and cheap internet access, it’s not uncommon for those people to try and make their own comics. I think, however, that it’s this burden of a panel that stops many amateur or independent comics from finishing. Some seem to stop right after they start because of the realization that each panel can’t just look cool. Panels mean so much more than that; they involve much more thought than that. Every artist, I believe, hits that wall when they realize that drawing a single panel is very hard work for something that they know and depend that the reader breeze right over. If the average reader doesn’t take in a panel with a single glance, understand it, and move on, then it’s likely you’re doing it wrong, and that’s scary to accept.

I am, by no means, a professional comicker (I may not even be a good one), though I am a thoughtful one. However, even that doesn’t mean I cheat when drawing a panel or get lazy every now and then and cook up a pose or angle I know will work or is simply easy to draw. Most importantly, I know I’m still learning. For some reason, I’ve decided to share that learning curve and its process with the world as my webcomic, Long John, hits the world-wide web.

I have some confidence already––having gone through a lot of public growing pains for the six years I co-wrote and drew Eben07––but this time Long John is all me, standing up creatively for myself for the first time ever. It’s a powerful moment, even if it ends up being a total disaster (which it won’t be––at worst it’ll be read by few readers: me and my mom). Before this, I only created in partnerships with other talented friends. But partnerships are ultimately temporary things as people grow and goals for creativity and life change. Through all that, I’ve studied and learned through all the ups and downs, searching for the right moment to become the artist I want to be. And that starts with Long John for all its strengths and flaws (of which it will have many).

However it may look, I’m not begging for readers or looking for sympathy because I think too hard about making comics or am having actualizing breakthroughs in my creative life. All I want, with hope, is that you’ll just read each update and ask, “Where’s the next one?”––overlooking the fear, sweat, thought, and intention behind every line and between every panel. Because that’s how comics are supposed to be.

Category:boasts of bethel

-- posted at: 1:00am PDT

Comments[0]

|

Thu, 26 June 2014

With Dan running at about 60%, Andrew boldly steps up to the reins and wheels a new episode through to the finish line. Under his masterly guidance, they competently discuss the following: Week in Geek - Andrew plays X-Com again. Dan plays Street Fighter IV for the first time. Boasts of Bethel - Dan discusses thinking about making comics too hard. Nerd Topics - Writer/director Rian Johnson was announced to helm episode 8 of Star Wars (and possibly episode 9), and with that news Dan and Andrew discuss the worlds of reboots and continuations and what it all means. Who Cares (title still pending) - The guys discuss a Doctor Who event that is particularly near and dear to Andrew as he had to say goodbye to his Doctor in a particularly gruesome fashion. They discuss Doctor Who: The Movie. Closing Time - Before getting to the new nerdly question, fans' answers to last week's question are addressed. But this week they ask: What nerd product/media do you feel represents or comments on its era? Why? What is your answer to this question? Leave a comment either at forall.libsyn.com, the posts on Facebook, or send an email at forallpod [at] gmail.com and your answers will be read on the next episode! It's an exciting week! For all intents and purposes, that's an episode recap.

Comments[0]

|

Tue, 24 June 2014

We're proud to announce that D. Bethel's new western webcomic, Long John, officially goes live today. Though nothing truly exciting has happened yet in the comic (it's just setting the stage this week), TWO pages have gone up. So, start at the included link and click forward to see both pages.

Category:general

-- posted at: 11:11am PDT

Comments[0]

|

Thu, 19 June 2014

This week, Andrew and Dan return with a bevy of new and exciting topics, including: -FTL -Super-old Doctor Who episodes -Long John, Dan's upcoming webcomic (June 24th at www.longjohncomic.com) -Dan Boasts about adaptations! -The boys discuss the return and legacy of adventure games. -Then they talk about the greatest game ever made, Final Fantasy III/VI -Other sundry topics! Our question to you, however, is what neglected gaming franchise would you like to see make a comeback and why? Leave a comment or send an e-mail to forallpod@gmail.com Until next week, that was a podcast (for all intents and purposes).

Music in this week's episode: -Stayin' in Black by Wax Audio -Prelude by Nobuo Uematsu -Fanfare by Nobuo Uematsu

Comments[0]

|

Thu, 19 June 2014

This Boast is framed around Game of Thrones and does not discuss content; so, there are no spoilers contained herein.

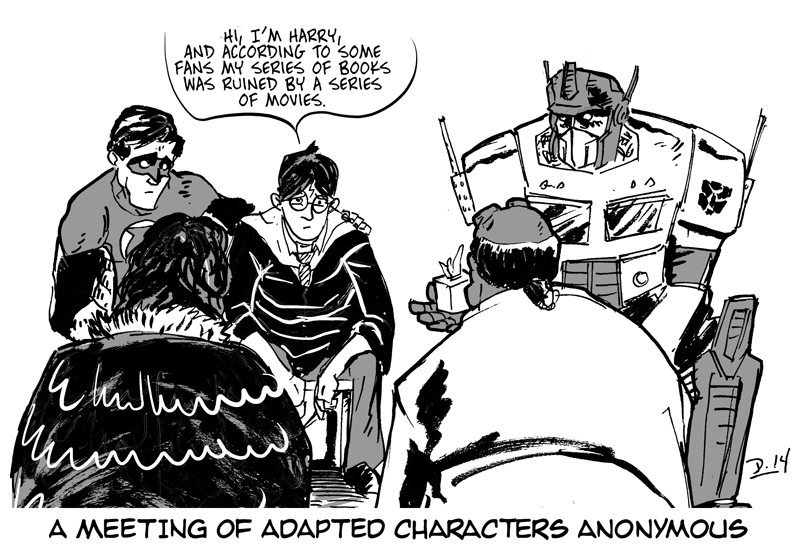

I like the Game of Thrones tv show more than A Song of Ice and Fire––the book series its based on––for a variety of reasons. First, each book has a page length that, at this point, can only be measured in scientific notation. At this point in my life, I have taken a firm stance and won’t read books over three-hundred pages (though exceptions can occur)––I’ve got too much else to do and my stupid brain isn’t able to remember that much story. Second (though related to the first), the ten episodes (at one hour each) that make up each season is the perfect amount for me to not only consume and still have time left in my day but to also remember everything that’s going on. I have my quibbles about the show, sure, but on the whole I enjoy it quite a bit. But don’t tell me to read the books, especially because they’re “better.” Of that I have no doubt. It is a fact that tv shows are terrible books because, by definition, tv shows are not books. However, the reverse is also true. Nerds’ slavish devotion to source material puts us into a strange quandary––we are super excited that our beloved stories and characters are getting adapted to other media––and, moreover, they’re super successful––but we also become obsessive hair-splitters who feel the need to declare that one version (usually the original) is superior to the other (usually the adaptation). I had to stop doing that because I wanted to actually enjoy these adaptations––especially when they’re good. My first major encounter with this “disappointment” was with Brian Singer’s first X-Men movie. Namely, how characters were shifted around in terms of relationships and ages for reasons that didn’t seem to make sense. The biggest offender in this regard was the character of Rogue who, in the comics, was the same age as most of the main cast and even had intimate relations with Magneto for awhile. For the movie, they basically made her a mixture of Jubilee (i.e., Wolverine’s teenage apprentice) and Kitty Pride (i.e., the new student at the school who is initially wary of being a mutant). Though I enjoyed the movie because, in terms of general characterization, Singer got the X-Men right, I made sure to note that it differed from the comics drastically (I am proud to say that I never cared about the lack of comic-inspired costumes, however). What turned me around was when I thought back to the X-Men cartoon from the ‘90s––another adaptation I was incredibly excited about. The series was extraordinarily faithful to the comics despite some dodgy animation and I remember being so excited for each episode to start on Saturday mornings that I couldn’t sit still. However, the feeling that dominates my memories of the show is mostly boredom. I eventually stopped watching it about halfway into season 3. It remained incredibly faithful and was even doing some direct adaptations of stories from the comics, but I just couldn’t bring myself to care. I realized that the show was too close to the comics, that I had already consumed this content but through a different medium––so why would I want to see it on tv if I have the comics in a longbox? Great artistic expressions are made by artists––that is, people who are adept at expressing themselves in a particular medium. A great comic book storyteller does not necessarily make a great film director or screenwriter (re: Frank Miller’s Will Eisner’s The Spirit)––a great director makes a movie great. If properties are being adapted into other media, I’d much rather see an artist of that medium approach the work so that the adaptation will mean something on its own and to not simply be “the movie version” or “the tv version.” Such requirements diminish the importance of the source material when being adapted. I point to things like the Hellboy movies––the second one, especially, feels right at home in Guillermo Del Toro’s oeuvre. I point to The Walking Dead––both the tv show and Telltale’s episodic video game series. I point to Darwyn Cooke’s Parker graphic novels. I point to Game of Thrones. All of these adaptations are done right––they focus on making a good example of the medium which is neither a “dumbing down” of a property to appeal to as wide an audience as possible, nor a point-for-point recreations of the originals. They want to make a good movie, game, comic, or television show first rather than just make the source material dance like a marionette. What makes a good book does not make a movie good. A good adapter knows that and works with the ideas, themes, and characters of the source material to make them as viable to the new medium as they were to the original. To do that may require changes, however, but if those changes are made out of the same desire to tell a good story––the same motivation as the original creator––then it should yield good results. Differences don’t make things bad––that’s called bigotry. Differences are just different, and as a fan it’s important to ask why––not just in terms of the story, but in terms of the medium.

The truth is the correlation between adaptations and their source material is more akin to alternate universes than family relationships. They rarely feed off on one another, especially once they get going. The choices one makes neither adversely nor, necessarily, favorably affects the other. They are separate entities and should be viewed that way. I’m sure the A Song of Ice and Fire novels have much more complexity and intricacy in terms of plot and character; I understand that. Game of Thrones, for a tv show, is just as wonderfully complex and dynamic––compared to other tv shows. And though A Song of Ice and Fire fans have been clamoring eagerly for book 6 in the series for three years––a book which will hold much more information and story than the tv show could ever muster––I’m comforted by the fact that I know I only have to wait a year for season 5.a

Category:boasts of bethel

-- posted at: 2:00am PDT

Comments[0]

|

Thu, 12 June 2014

We're back for episode three! This week Andrew and Dan get into trouble talking about topics such as: -Andrew's recent decent into Bronyhood...sort of. -Dan left his house, for once, to see a movie! -Dan also talks about "next gen" gaming. -Then they come back to talk about the indie game movement, spurred on by this Gamasutra article. -To right this vehicle, they then talk about Doctor Who again, this time discussing the 2nd Doctor's exit story, The War Games. -Yes, they know E3 is going on right now. No, they don't talk about it. As always, they would like to hear from you about what you thought of the episode! You can do that by leaving a comment at the episode page, found at forall.libsyn.com. You can also send them an e-mail at forallpod [at] gmail.com. For all intents and purposes, this is a blog post. Music from this episode includes: -Stayin' in Black by Wax Audio -I Am the Doctor by Jon Pertwee

Comments[0]

|

Thu, 12 June 2014

Console-based video game fans are in a strange state right now. In the virtual vacuum between console generations and good games, we tend to become very loud in our uneasiness. When Sony and Microsoft’s new consoles––the Playstation 4 and XBox One, respectively––hit the market last November, the reigning console generation––being comprised of Sony’s Playstation 3 (PS3), Microsoft’s XBox 360, and Nintendo’s Wii––had lasted eight years, the longest console cycle modern gaming had seen. The previous generation’s viability is unprecedented, though, because amazing games that pushed unforeseen limits of these machines were being released right up to the end. The PS3 and 360’s long lifespan consistently upended modern console gaming by setting new standards and growing despite being, ostensibly, the same hardware throughout that time. Everything from the rise of the first-person shooter (FPS) and the open world to the necessity of on-line multiplayer, from cover systems and branching trees of “morality” to the acceptance of smaller, independent games––the definition of modern gaming kept getting re-written despite the technology staying the same. What’s important is that this redefinition happened organically over time; certain games, for some reason, were able to pierce the walls of expectations and technological limitations and forced everybody else to jump onto that train. Before this generation, the defining moments were limited to perhaps one or two major upheavals per console. By virtue of the fact that this generation lasted so long is impressive in its own right, but it does set a precedent that game-changers (pun intended) need to happen often. The console gaming culture endured so many sea changes during the previous generation that when the new consoles were announced an interesting phenomenon occurred; the community began trying to codify what “next gen” gaming was, a tendency that became amplified after their release. This tends to center around the tired “which console is better” debate, and people who have already picked sides end up just yelling at each other. Some of this discussion focuses around technical aspects of the new consoles––that is, what’s under the hood and how games perform in terms of frame rate and resolution. Microsoft itself tried to define the future by incorporating a gordian-like integration with a customer’s cable tv into the XBox One. All of this empty rhetoric feels about as respectable and respectful as a dogfight because frame rate does not make a good game, neither does resolution, or graphics, or the controller, or the manufacturer. What’s ignored in all of this is the emotional and cultural resonance the experience of a truly revolutionary game has when it hits the community. Think of Super Mario Bros., or Sonic the Hedgehog, or Metal Gear Solid, or Shadow of the Colossus, or Halo. These games are among the pantheon of gaming experiences and industry turning points because they felt like they mattered. Combine those expectations with the first round of games that the new consoles are seeing: most are just higher resolution versions of games that are also available for the previous generation; the exclusive new console games seem to be merely more powerful iterations of games that could be released on the older consoles, though, obviously, not as impressive. Many are sequels in franchises started in the previous generation. Aside from barely exploiting the technical advances, these games––so far––are offering nothing truly new. But I don’t think that’s a problem. As with any generation, innovation comes with comfort. The new consoles are just that, and the frames needs to settle before they feel like home for developers and players. However, the question is continually asked: when are we going to see some next gen games? I think that’s the wrong question, however. It’s short-sighted and hubristic. It’s not a matter of when they are released––it’s not like they’re being hoarded. The question to ask is, “what are next gen games?” The best and scariest part is that we won’t really be able to answer that question until this young generation of consoles ages and is ready to be put to pasture. No matter how much a person can learn about the technology or study the past, the simple truth is that we don’t know what will come to define this generation of gaming because the needs of gamers change with the society that they live in. Making predictions is just making wishes. The defining characteristics will come with time, out of the blue, and will change the scene around them. It’ll do what Gears of War, Uncharted, Call of Duty: Modern Warfare, Assassin’s Creed, Portal, Batman: Arkham Asylum and Braid (among many, many others) did for this generation. Trying to assert what “next gen” gaming is now is like proclaiming that a baby is going to be president. More disturbingly, if you are trying accurately to define what next gen gaming is right now, then you are depriving yourself of the most enjoyable part of playing games: discovery.

As gamers, we need to let ourselves be surprised again, to allow ourselves to walk into the future blind and just play games that developers want to make. To force definitions on the industry only creates undue pressure; that’s why we get an Assassin’s Creed game and a Call of Duty game every year. That’s why Rock Band and Guitar Hero don’t exist anymore. They became exhausted properties because they gave us what we thought we wanted, and they thought what we wanted was not innovation and progress. But then a LIMBO, Journey, Brothers, or The Last of Us shows up and proves that we don’t know anything. And then, for a few brief moments, the yelling stops because we’re too busy having fun again.

Category:boasts of bethel

-- posted at: 6:00am PDT

Comments[0]

|

Thu, 5 June 2014

This is an expanded version of the Boast of Bethel heard in Episode 2 of A Podcast [ , ] For All Intents and Purposes. One of the questions fans of weird writer, H. P. Lovecraft, are always asking revolves around “faithful” cinematic adaptations of Lovecraft’s work. There are a few that ardent fans can get behind, such as the very literal adaptation of “Call of Cthulhu” by the H. P. Lovecraft Historical Society––but, then again, it was a 90-minute, black and white, silent film adaptation meant to mimic the types of films available at the time the story was published, in the late twenties. But it is quite a literal re-telling of the famous story and, for all the nested narratives and low-budget aesthetic, it’s a pretty good time. On the whole, specific film adaptations of Lovecraft’s work are more up to a viewer’s personal taste than cinematic quality. It’s hard to balance what fans tend to want––a majority of which want a horror film––and what Lovecraft was trying to do––to create a sense of reflective, psychological terror. The thesis Lovecraft stuck to over the course of his short but prolific career focused on the idea of cosmicism––that humanity is rather small and ineffective in its place within the universe––and, through his admiration for writers like Poe, Chambers, and Blackwood, tried to alternately find the horror and the terror in such a concept. The distinction between the two goals is that horror tries to frighten its audience either with monsters, action, gore, frightening scenarios, etc.; and terror is the sinking, hopeless, and helpless feeling generated by the content or theme of the story; that is, even if a story itself is not horrific, it can be terrifying. Though Lovecraft is known for his tentacled monsters, overwritten prose, and not-so-subtle racism, what he excels at––and why he’s remembered––is that there is really no better place to go for a story about cosmic insignificance that’ll warp your dreams even if you don’t find his story particularly effective. Because Lovecraft is so focused on crafting an oeuvre that explores the realm of humanity’s inefficacy––and how humanity deals with that––not a lot happens in his stories and his characters aren’t that interesting. Lovecraft’s most famous monsters are, for lack of a better explanation, unavoidable natural disasters. They are natural creations of the universe but on a much larger scale than humanity can even comprehend. So, even though Cthulhu’s general image is of an overgrown destroyer of cities, Lovecraft makes it clear that it’s not out of malice, noting in “The Call of Cthulhu” that Cthulhu and his kind are “free and wild and beyond good and evil[.]” Everything Lovecraft writes serves this theme. In that sense, his stories are more akin to preaching than engaging fiction. Aside from a few stories––“The Dunwich Horror,” “Shadow Over Innsmouth,” and perhaps “The Case of Charles Dexter Ward” being the notable exceptions were they to have the director, writer, and budget behind them––Lovecraft’s stories work best as prose and not as literal translations into other media. We know because it has been tried since the sixties. Like a good sermon, however, his themes are infinitely applicable. This is why I would argue Lovecraft is not as culturally viable as fiction which is Lovecraftian. For what they do more than for what they are, Lovecraft can excel in other forms other than written prose only when those creators take that philosophy and do something unique and engaging with it. Standouts include John Carpenter’s The Thing (yes, it is based on a novella by HPL contemporary, John W. Campbell, but the close connections between Campbell and HPL and of his novella “Who Goes There?” and “At the Mountains of Madness” makes for some interesting research), Ridley Scott’s Alien, Frank Darabont’s The Mist, and the Joss Whedon project of The Cabin in the Woods, but none are literal, nominal, nor ostensible adaptations of Lovecraft’s work; they are all imbued with his sense of cosmic indifference, though, which makes movies that, while often horrifying, terrify their viewers long after the credits roll. Another worthy addition to that list of fine Lovecraftian films is Gareth Edward’s Godzilla. The movie has been generally divisive, especially among Godzilla fans, of which I don’t necessarily consider myself a member. But I’m not arguing about whether it’s a good Godzilla movie––though I think it is. My Godzilla credentials are limited. The only legitimate Godzilla film I’ve seen is the redundant American release of the 1954 original (and ignoring the 1998 Matthew Broderick vehicle). Despite the strange narrative approach, the social commentary of the original movie is profound even sixty years later. I don’t think it hurts to say that rubber monsters slapping each other doesn’t interest me very much––there’s a reason why most Godzilla and Godzilla-like movies are fodder for Mystery Science Theater 3000––and the original Godzilla is not that at all. The creature is a walking metaphor, a theme on stubby legs which represents man’s hubris at playing with science it didn’t truly understand. The creature is a lurking Japanese memory of the war, of foreign catastrophe and, perhaps, even guilt. Despite being a man in a rubber suit, the original Godzilla is a wholly appropriate post-war statement. One which breathes fire. Going into Edward’s Godzilla, I secretly yearned for a Godzilla that meant something rather than just a two-hour wink-nudge to kaiju fans. Luckily, even though this Godzilla is drastically different in story, origin, and scope from its predecessors, it is a Godzilla for the modern age. More personally important, it makes Godzilla a Lovecraftian force of nature. The ties between Godzilla and Cthulhu aren’t strained: a creature that sleeps at the bottom of the ocean, to surface indeterminately and cause wanton destruction is an apt description of both creatures. More than that, however (and where this Godzilla departs from its original incarnation), is that this creature is divorced from humanity completely. No longer is Godzilla a by-product of human ignorance; Godzilla belongs to a time before man, an earthly inhabitant arguably more native to the planet than humanity’s claim to it. More than that––bad writing aside––Godzilla and its ilk in the new movie are unpredictable and unstoppable forces of nature; to them, humanity means nothing. This Godzilla doesn’t pick sides because it is neither “good” nor “bad”; it is, as Lovecraft said, a “free and wild” creature which is “beyond good and evil” because it is not recognize humanity’s moral constructs––rules that we created to get a long with each other, not with nature. Like any Great Old One, a viewer would wonder if Godzilla even really notices the humanity it stumbles over; perhaps it sees so much change between its periods of consciousness that it just assumes buildings and elevated train tracks are this era’s forested hillsides. That is what matters, though; we don’t know (though the movie does let us down by having Ken Watanabe correctly guess everything, which is dumb). And in that ignorance, in that incomprehensible modus operandi, Godzilla becomes undeniably Lovecraftian because not only does humanity not seem to matter to the creature, but the movie makes it clear that there is nothing humanity can do to make it matter. We throw militaries at it and nothing noticeable nor important happens. It walks through skyscrapers like a horse through grass. In the end, all humanity can do is hope it survives this unavoidable and inevitable cataclysmic natural disaster. Call it an action movie or monster movie, but––for all it could represent in the modern political strata––one thing Godzilla can safely be called is Lovecraftian because of the creature and all of its implications: Godzilla destroys, yes; that’s horrifying. What’s terrifying is that Godzilla waits.

Category:boasts of bethel

-- posted at: 12:30am PDT

Comments[0]

|

Thu, 5 June 2014

As expected, we have created a second episode for your listening pleasure. This week, as with last week, our topics went all over the place: -Andrew discusses his time with the game, Sentinels of the Multiverse. -D. Bethel discusses his new webcomic, Long John (longjohncomic.com). -He also boasts about how Godzilla could possibly Cthulhu's second-cousin. -Andrew gives us all we need to know about the new Dungeons & Dragons. -In a new segment––Love the Craft––the boys discuss the H. P. Lovecraft story, The Shadow Over Innsmouth. -To close out the episode, they take a look forward and ask if they have anything exciting planned for the coming week. (SPOILERS: No.) Please feel free to leave your thoughts on any of the above topics and we'll read it on next week's show! Also, FAIAP (For All Intents And Purposes, that is) is now available for subscription on iTunes if you prefer to get your podcasts there. If you prefer e-mail, that is at forallpod@gmail.com Thanks again for the great response to the show! We aim to entertain!

Music from this episode includes: -Stayin' In Black - Wax Audio

Comments[4]

|

Wed, 4 June 2014

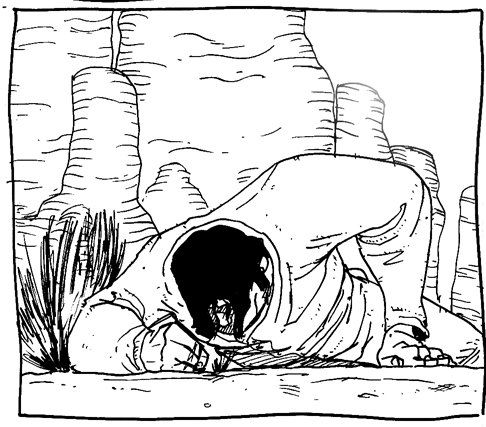

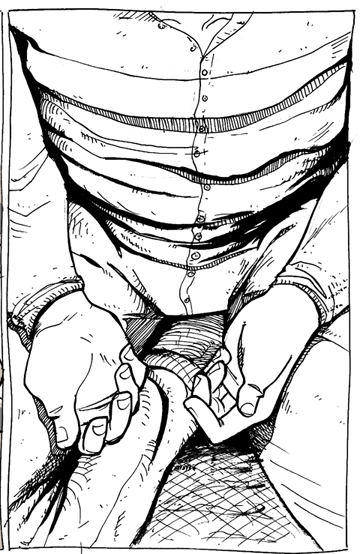

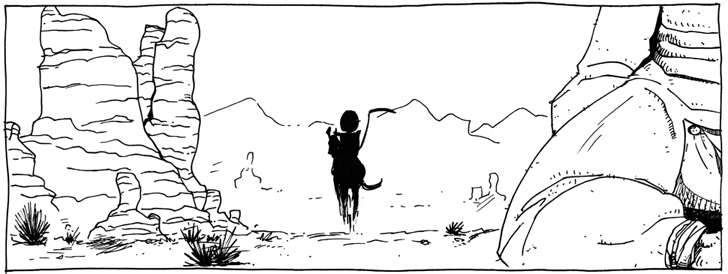

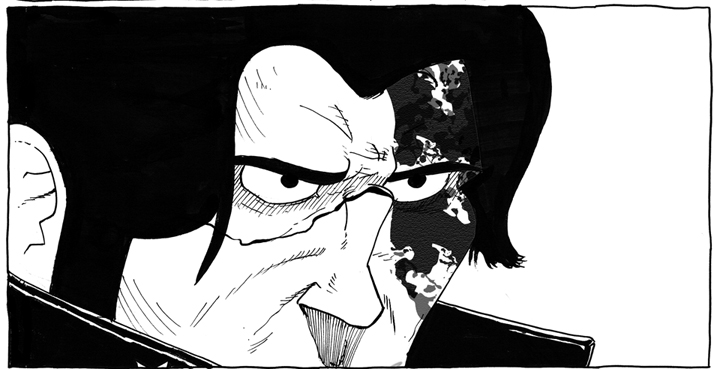

After six years of comicking, Eben07 co-creator, co-writer, and illustrator, D. Bethel, is launching his brand new long-form webcomic at the end of June with Long John.

Long John is a story about a famous gunfighter who wakes up with nothing but his long johns, a gash in his head, and a visit from a mysterious, threatening figure called the Hellrider.

A western webcomic with a noir mystery, a revenge story, and an existential character study mixed into it, Long John. Though it does not contain any robots, mutants, spaceships, zombies, magic, or aliens, the interesting characters, unforgiving setting, and Long John's story will keep you yearning for the next update.

While not a comedy like Eben07, fans of that comic ore of D. Bethel’s art style will not be disappointed with his new direction with Long John. Fans of both fast action and slow character moments will find a lot to grab on to as we follow Long John Walker on his quest to find out not only what happened, but who to pay back for doing it.

Long John starts updating on Tuesday, June 24th, 2014 and will update regularly twice a week with short breaks between chapters. Head to longjohncomic.com to find out more.

Category:general

-- posted at: 12:00pm PDT

Comments[0]

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||